And Donor Makes Three

How to explain assisted conception to your child

Most parents get a little nervous the first time their child asks the question, "Where do babies come from?" Usually the answer can be straightforward, something like: "When two people love each other they can make a baby together." This answer is short and sweet and often enough to begin the ongoing conversation about intimacy, sexuality, and family most parents hope to have with their children as they grow.

But when a child was conceived through donor conception – egg or sperm – the question and the answer are a bit more complicated. And although it might make you squirm, this innocent question is an important step in a child's journey to understanding himself and the people around him.

What is donor conception?

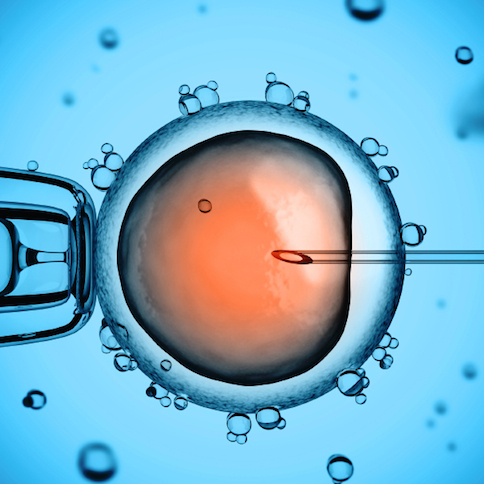

Donor conception means using a donated gamete to conceive a child. A gamete is a reproductive cell, such as a mature sperm or egg, capable of joining with a gamete of the opposite sex. This produces the fertilized egg that will grow into an embryo, then a fetus, and eventually a baby. Families choose donor gametes when there is no other way to conceive a child or if a parents' DNA increases the risk of passing along a life-threatening genetic condition.

Some other reasons for using donor conception include: infertility (which affects about 10 percent of the population), advanced maternal age (being older than 35), being in a same-sex couple, and choosing to have a child without a partner.

Should kids know?

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine recommends families explain the use of donor conception to their children because research shows that secrecy about a child's origins is generally detrimental to a child's mental health. When the need for donor gametes is most obvious (like in families with gay or lesbian parents), children typically grow up being aware of it. For parents who've experienced infertility, qualms about how to start this conversation can sometimes get in the way of telling their children.

Why some parents postpone

Discovering that you cannot conceive a child without a donor gamete is a life- altering event. At best, it's a significant emotional adjustment, and at worst, it's a trauma. Many parents are busy with their own internal conversations about donor conception as they move slowly toward acceptance of this new reality. And parents' thoughts and feelings about the decision may remain unresolved even after the baby finally arrives. So it's natural to be nervous talking about it when that baby is old enough to ask.

Other parents may put off the conversation because they worry it could be painful and stigmatizing for their children and for themselves if the news becomes public knowledge. (And anyone who's ever told a 4-year-old anything knows it may soon be broadcast widely.) And for many families, talking in specifics about the donor can be strange and uncomfortable – especially because many families have little information.

Why parents shouldn't wait

When parents delay talking with their children, they miss the opportunity to make donor conception one of the basic things a child knows and accepts about himself from a young age. By hearing their story early, children are able to learn the intricacies and implications of assisted conception over time (rather than having to digest a lot of new information at once), just as they learn about so many other things that define their families and themselves. It becomes a natural part of their story.

4 tips to talking about donor conception with your child

Start early. When you begin the conversation early – even before your child can understand the specifics – it gives you time to get used to talking about donor conception. You also have the chance to identify and manage any painful feelings that remain from the decision to use a donor, and you will get practice telling your story. Soon it will come naturally to you and get easier to tell.

Remember that children will be curious. Children will approach the idea of donor conception with interest because they have no preconceptions about what is the "right" or typical way to be conceived, or who "should" be in a family. That's a good thing. It will remind you that what truly matters is the inquisitive person in front of you who resulted from your efforts. It also means you don't have to spend a lot of time trying to justify the situation. For them, it will just be another part of the world that you are explaining to them.

Keep it simple. Explain that three things are needed to make a baby: a special cell (sperm) from a man, a special cell (egg or ovum) from a woman, and a special place inside a woman's body for the baby to grow.

Also explain that sometimes these three parts come from the two people who will be the baby's parents, and sometimes another person is needed to help make the baby. It is possible that two or more people, called donors, may be needed to make a baby. If you want to, you can talk about the donor that helped your family and share any facts about him or her.

Emphasize love. Let your child know how much you and her other parent love each other and how that love gave you the determination to create a family. Or, for single parents, how you had so much love to share that you worked hard to create your child and your family.

Though it's great to start early, it's also never too late. One study about how adolescents perceive donor conception suggests that teens are able to empathize with their parents' effort to create a family. The teens recognized the difference between a parent and a donor and were aware that donor conception did not change the role of parents in their children's lives. In the study, the teenage participants felt strongly that children are entitled to this information because it's relevant to their identity.

And they are exactly right. Families begin when parents conceive the idea of a child. The child grows first in the mind of each parent as they make plans to get pregnant and dream about the future. So when children ask where babies come from, they are also inquiring about your thoughts and feelings during the process. In essence, they are asking, "How did you decide to bring me into your family?" What they most want to hear from you is, "Listen, this is the story of how I began to think of you! This is the beginning of our family."

A version of this article originally ran on Psychology Today and is reprinted here with permission from the author.