Fighting Cancer and Freezing My Eggs

Trying to save my fertility as I saved myself

My first college boyfriend gave me chocolate-covered strawberries for Valentine’s Day. The strawberries tasted tart under elaborate swirls of black and white chocolate. I frowned. “Well,” I thought, “onward and upward. I have the rest of my twenties for better gifts and boyfriends!”

Three years later I would have given anything to receive these strawberries again. Instead, I sat in a cold waiting room and stared at one dangling heart over by the assistant’s desk. Women glanced at me, curious about my boyish haircut and my mother, who had accompanied me. Neither one of us seemed to fit the patient profile. Soon enough those anxious faces returned to their clasped hands, twirling their wedding rings, waiting for their names to be called. Most of them were at this Upper East Side fertility clinic on Valentine’s Day for their IVF treatments. I was there to meet the doctor who would surgically remove and preserve one of my ovaries.

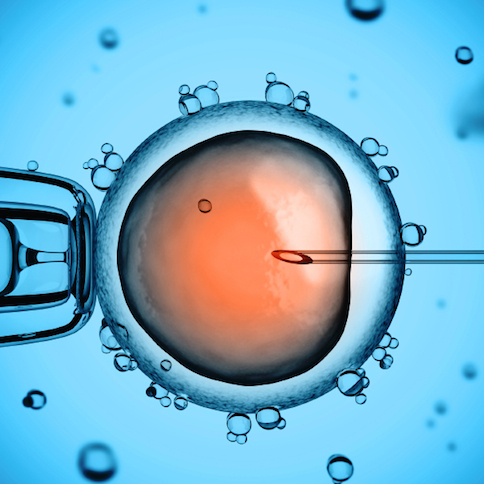

Four days earlier I had had my first cycle of chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Chemotherapy kills the body’s most rapidly dividing cells—including cancer, hair follicles, eggs and sperm. In just one cycle of chemotherapy, my fertility had plummeted to that of thirty-year-old, and with seven more cycles of chemotherapy to go, I would likely reach menopause once my treatments finished—if my treatments finished. Weeklong series of injections of Lupron and egg retrieval would have delayed my treatments, so instead I benefited from a novel fertility preservation technique, ovarian tissue cryopreservation.

A few hurried phone calls and one doctor visit later, my laparoscopic surgery was scheduled and I was being wheeled into New York Presbyterian Hospital. In the operating room the atmosphere was relaxed as doctors prepped for the surgery to the tune of Kelly Clarkson playing on a radio nearby. I looked at one of the interns who was about my age, the kind of guy I would have gone for in college. He looked at me and then averted his glance. I was no longer that healthy college girl but a patient in a robe and short hair, going over some high medical precipice.

I felt awful when I woke up, a mix of the residual chemotherapy and the anesthetic. I couldn’t bear to look down at my belly button and below, but there was nothing to see—the areas were neatly bandaged. There were only three minor incisions, one at the crease of my belly button and one above each of my ovaries. I never took any of the prescribed post-op painkillers and some forty-eight hours later was onto my next cycle of chemotherapy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering. I was relieved that the surgery was behind me and that one of my ovaries was safely tucked away as I faced the rest of my treatments.

As my treatments increased in duration and aggressiveness, I had days when I felt I could not face another deluge of medical tests, opinions and treatments. I became so anxious that I threw up before chemotherapy or when I talked about it. I was prescribed sedatives (Ativan) ahead of most hospital visits, and my anxiety eased. But when my day still felt too overwhelming, I tried to remind myself to take things a minute at a time—instead of a day at a time. There is no point worrying about your next doctor’s appointment when a nurse is taking your blood pressure.

Today my ovarian tissue is preserved in a cryogenic tank, a concept that felt rather abstract until I had to personally move the tank from one hospital to another a few years ago. “Who else are you going to trust to move your ovary around?” my doctor had asked. I hadn’t quite realized how heavy and big a cryogenic tank is—triple the size of a diver’s oxygen tank—until I lugged mine across town in a Yellow Cab to its new home, Manhattan CryoBank.

I try not to dwell on what that cryogenic tank might have in store for me down the road of marriage and children. After all, just a few years ago I could not have fathomed that a cryogenic tank would dwarf all my other Valentine’s Day gifts.