Accepting Childlessness After Infertility

How I found my place in a motherhood-mad world

My early adult years unfolded with the usual milestones: dating, new jobs, marriage. But then, one by one, my girlfriends sent out baby shower invitations, and our life experiences diverged. The majority moved down one path – motherhood – while others decided with certainty that parenthood was not their dream. My path wasn’t quite so clear. After a year of carefully timed sex with no positive home pregnancy tests as a result, it slowly dawned on me that fertility operated on a much broader and grayer spectrum.

This isn’t what they told me in high school

With increasing trepidation, I realized my body wasn’t operating as advertised. Month after month, my self-esteem eroded. Hopeful at the beginning of each cycle, I’d regress with the bloody reminder of my failure. The primal urge to procreate grew stronger as the months slipped away, driving me to seek out any and all knowledge available – alternating between Eastern and (more expensive) Western medicine in a frenzied attempt to fix what was broken.

First, I had a hysterosalpingogram (HSG) to rule out blockage of my fallopian tubes, while my husband underwent sperm tests. We both made diet changes, and I added a new move: elevating my pelvis and legs in the air for 30 minutes after sex, all the while trying to “just relax.” Several cycles of the fertility drug Clomid led to two laparoscopic surgeries to combat endometriosis.

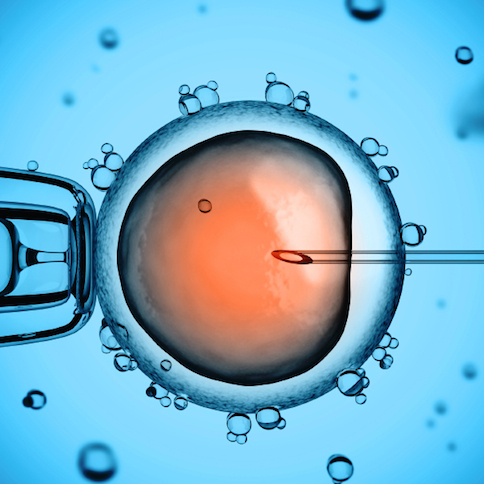

Over the next few years, I submitted to multiple intrauterine inseminations (IUI) combined with Clomid and prescreened sperm. I also added Chinese herbs, yoga, more diet changes, chiropractic adjustments, and large amounts of red raspberry leaf herbal tea. Finally, we had saved enough money for the expensive and most complex of the fertility treatment regimens we attempted: intracytoplasmic sperm injection in vitro fertilization (ICSI IVF) and subsequent frozen embryo transfers (FETs) coupled with acupuncture.

During this decade of fertility treatments and unsuccessful attempts to conceive, baby bumps and mom’s clubs became all the rage. I found myself a misfit with no social support network. My sleep-deprived friends – up to their ears in diapers and envious of my free time – had little understanding or patience for my growing anxiety, while my acquaintances who are childfree by choice questioned why I’d ever consider submitting to extraordinary measures to conceive.

Alone, I grappled with a life that might not involve motherhood, using the time between treatments to invest in graduate school and more challenging work assignments. I tried to reassure myself that I was more than my reproductive organs, but I was locked in a zero-sum game. My identity and femininity were tethered to my reproductive failures.

One night I typed infertility blogs into a search engine, and a new world opened up to me. There, congregating online, were all manner of “infertiles” decrying the insensitivities of the “fertiles.” While not a community I took any joy in joining, there was comfort in being part of a recognized tribe. I reveled in being among women undergoing the same onerous, dehumanizing experience.

Finding a way out

These were my sisters in struggle as my husband and I went for one more IUI, one more round of acupuncture, and one more blood test to determine if there was a new factor we hadn’t considered. But finally, strung out and wondering how we would possibly cope with another failed cycle, I started to separate from my sisters. I allowed myself to imagine a life not driven by 28-day cycles and heartbreaking vigils. After exhaustive (and exhausting) conversations, my husband and I loosened our tight grip on our fragile dream.

We were tired of living in limbo, and the heartbreak of losing more alpha pregnancies and IVF offspring was too much to bear – especially when most of the world didn’t recognize our losses or offer any of the support reserved for legitimate grief.

Back to being a misfit

Infertiles and the $3 billion infertility industry are driven (for different reasons, obviously) toward one outcome: successful pregnancy and delivery. That’s where the attention and assistance is focused. There is, I learned the hard way, a rough landing for those who decide to end treatment (usually due to financial or emotional strain).

We’re expelled and left to find our way back to some kind of normal within a society that celebrates motherhood, and we’re surrounded by parents preoccupied with childrearing – at work, on newsstands, on TV, and on the Internet. Even the once infertile woman who felt put upon by her more fertile friends, once pregnant, morphs online into a person besotted with baby care and concerns.

Those of us who opt out don’t want to be pitied by society, but also don’t want to seem (especially within the infertility community) like we didn’t want it bad enough.

Grieving and moving on

In making sense of and sharing what I’ve learned about disenfranchised grief (grief that is not acknowledged by society), I began to actively mourn the losses we’d endured and found peace. By giving voice to my experience, I tapped into a well of strength and resilience and cultivated a community of women whose lives don’t involve parenting. We see families of two where we used to see couples.

Today, birth announcements or photos of newly pregnant, aging celebrities in the supermarket checkout stand no longer evoke envy or anger. I’ve learned to appreciate my body, my life, and my relationships in a new light. Still there’s awkwardness when meeting people with children for the first time, who routinely inquire if we have any of our own (where to begin?) or when hanging out with friends who chat about the challenges of raising a family. For my part, I tread lightly in our newfound joy and our life lived without the limitations they face so as not to appear indifferent to their struggles and the demands on their time.

My husband and I continue to push forward, to shape and define a life outside the beaten path. We challenge each other to uncover new possibilities, to seek new adventures and discoveries that will enrich our understanding of the world and our place in it. That’s what we would have encouraged our children to do.