Saying Goodbye to My Frozen Embryo

How I made an emotionally complicated decision after infertility

There was a short message and attachments – two blank forms with the details intended to help me and my husband make a major life decision: what to do with our frozen embryo.

For 22 months, our embryo had been stored at a Manhattan fertility clinic as we raised our then 1-year-old twins and their 3-year-old brother in Brooklyn. But our insurance was about to change, increasing the cost of storage prohibitively. So we decided the time had come to remove it from its suspended state.

We could use it ourselves (an option that wasn't really even on the table as we scrambled to raise three kids). We could donate it to another infertile couple. We could allow it to be used for scientific research. Or we could simply thaw and discard it.

These options were presented in a straightforward manner on the forms, but I felt a rising panic as I read them. I closed the documents and decided to bring it up with my husband another time. Weeks and then months passed, and the forms remained untouched and unprinted, but never forgotten.

Long before we faced this decision about our frozen embryo, my husband and I spent 17 frustrating months trying to conceive our first child. I went through a battery of invasive tests followed by a trio of unsuccessful inseminations. I did acupuncture, took Chinese herbs, and practiced yoga. With no clear cause of my infertility, my doctor performed an exploratory surgery, during which he discovered and removed the endometriosis that was choking my fallopian tubes. A few weeks later, I was pregnant.

When my older son turned 1, my husband and I decided to try to conceive again. I thought I might get pregnant naturally, but I didn't. After a year of using fertility drugs and going through more unsuccessful inseminations, we started our first in vitro fertilization cycle, right after my son's second birthday.

IVF is the last stop on the infertility express. It's expensive ($14,000 in our case, which we pulled from the last of our savings), exhausting, and both physically and mentally draining. During my 28-day cycle, I first gave myself daily hormone shots to stimulate my ovaries and then others to keep them from prematurely dropping their bounty. My belly became sore and swollen. I felt like a living pincushion.

Two weeks in, seven mature eggs were retrieved. Five were fertilized, and four were still thriving after three days, when the embryo transfer took place. Because I was young (32 at the time), we had the option of transferring one or two embryos. In the interest of improving our odds, we decided to use two, hoping one would take.

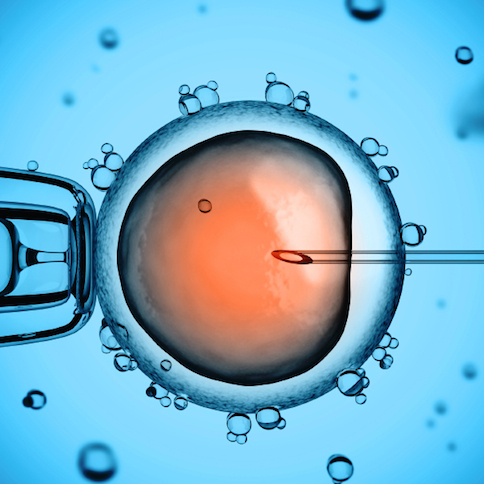

As my husband headed into the waiting room, I hopped onto an exam table in the same sterile white room where my eggs had been harvested a few days before. With my legs spread and feet in stirrups, the doctor showed me our two chosen embryos, illuminated on a screen to my left. I still remember them today, two haloed, brain-like masses with thin overlapping circles, or cells that seemed to glow with life. They were stunning. And even then, they felt like my babies.

And then they were sucked up by a pipette and transferred by thin rubber tubing into my uterus, where they settled in and grew. Just 20 days later I saw them again, now visible on an ultrasound. Two more weeks passed, and I heard their heartbeats thump strong and almost in unison. And in no time they were here. Those embryos became my twins, now healthy, exuberant toddlers, who are quick to crack a joke or burst into song and dance.

But this story isn't about my kids. It's a story about what was left behind. Those two remaining embryos were allowed to grow for a bit longer, and another one developed into a blastocyst (about 100 cells that were just starting to differentiate) when the clinic flash froze it at five days. It was our insurance plan, and it joined more than one million embryos that look just like it, stored at sites across the country.

And now, the paperwork that would decide the fate of that embryo sat in my inbox – the decision about what to do with it haunting me.

I cycled through unexpected and intense feelings of guilt and sadness. I relived our entire infertility journey, all the exhaustion and emotional turmoil and expense. I considered whether I was ready to shut the door on the possibility of having more children, or whether it'd be better to use the embryo and attempt to get pregnant again, putting off my career goals for a few more years if things worked out. I did all this thinking without ever consulting my husband.

Still undecided and emotionally worn out, I finally started the conversation one night in September when our kids were asleep. For him, the decision was simple. He didn't want any more children – actually, we didn't want any other children, he reminded me – and with our new insurance, it would cost more than $1,000 a year to store the embryo. This was way more than we were willing to pay, he said, and a clear sign that we needed to figure out how to let it go.

I knew he was right, but I remained confused and angry about the whole situation. "How had we never discussed all of this before we decided on IVF?" I kept asking myself. Looking back, I think I'd been so determined to get pregnant that I never took a minute to look ahead to this point in time. Even though I may have ended up in the same place either way, I wish that I had.

I printed out the forms.

Some couples choose to donate their embryos to another family, but both of us felt this was not for us. Assuming everything went well, it would be our biological child raised by strangers, and that was not something we were willing to consider.

Donating the embryo to scientific research somehow felt wrong too. Although intellectually I understood that the studies designed to learn more about embryo development are important, even necessary, to improve future IVF outcomes for other couples, I didn't like the thought of experiments being conducted on a little piece of us. My husband agreed.

Since we'd already decided that we wouldn't use it to try and get pregnant, we were left with one option: We thaw and discard it. And this is what we chose.

We filled out and signed the paperwork later that month, and when I dropped those forms in the mail, I knew we'd made the right choice for our family. But I also felt conflicted. Two years later, I still do.

When I try to pinpoint where those feelings are coming from, I always return to the snapshot of my now 3-year-old son and daughter when they were each just a handful of cells in a petri dish. Unless you've also done IVF, you'll likely never see anything like it. (Most women don't even find out they're pregnant until around 14 days after conception, when a pregnancy test registers positive.)

But I saw that beginning of my twins' life, and just as I have ultrasound printouts and hundreds of pictures taken of them together over the years, I also have that picture.

Seeing it – and knowing what they turned into – changed me.

I wish my husband and I had prepared ourselves for this decision. And I encourage everyone who is going through IVF to consider having this conversation before beginning the rounds of injections and insertions. We should all be discussing these issues and coming up with better ways to support families that have to make this choice. More than 190,000 IVF cycles were performed in 2014. Many of the couples involved will end up exactly where I did.

But even though I'm advocating for more openness around this topic, I rarely talk about this experience with friends, even those considering using assisted reproductive technologies. It feels like one of those things that unless you've gone through it, you may not understand. This is my effort to put into words what the experience meant to me.

I worked hard to create my family. They are everything to me, and I feel thankful every day that I get to live this crazy, complicated and love-filled life with them by my side. But I still think about that embryo. It was our chance for a fourth child, and letting go of it (and that possibility) was an unexpected loss that I continue to mourn.